Clémentine found the dream studio in 2019. We already had a studio for our creative work, but we needed another one for the publishing house we had founded: Grammatical. Drawings, paintings, and ceramics would also find their home there.

During our first visit, we were utterly captivated by the charm of this place and our future studio: Number 21.

But what we didn’t know at the time was the rich history—or rather, the many stories—of this legendary Parisian place and its global artistic influence. Our studio had once been home to many others and had welcomed even more such as Modigliani, Picasso, Klein…

Number 21

The 21 avenue du Maine was once a post house where the horse teams were changed for those traveling to Brittany. The only visible remnants today are the two stone markers at the end of the alley, which were originally located on the avenue. On January 19, 1869, Jean-Adolphe Roux, a lawyer at the court, became the owner of all the buildings. In 1868, before entering the passage, the coal merchant Gabrillargues occupied the right-hand shop, and Mr. Lepage, a cooper, occupied the left-hand shop, succeeding Mr. Drouville. The walls were made of frames and cladding covered with tarred cardboard. As early as 1899, the owner modernized the place by installing a complete sewer system, completed in 1901 by the architect Mr. Charpentier. After his father’s death in 1899, Joseph Roux decided to transform the place into an artists’ community. In 1900, he acquired a series of pavilions from the Universal Exhibition. The buildings were restructured, and the use of metal beams gave it an industrial character. In 1920, the Roux family sold the alley to Eugène Philebert Maisonny. In 1922, the roofing company of Etienne Maisonny moved in. In 1946, one of his descendants, Madame Lynka Maisonny, became the owner. Upon her death in 1990, faced with high inheritance costs, her children were forced to put Number 21 up for sale. The Town Hall of the 15th arrondissement preempted the property and presented a real estate project in 1992. This project was rejected by the residents of the alley. The association “Friends of 21 Avenue du Maine,” presided over by Maurice Tinchant, was supported by many artists and personalities, including Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, Robert Doisneau, Juliette Binoche, and Frédéric Mitterrand. A petition circulated, the press took up the issue, and a long battle ensued. In 1996, after two successive legal appeals, the City of Paris agreed to abandon the total destruction of the alley and preserve part of it. The creation of the Montparnasse Museum in the preserved premises of Marie Vassilieff was proposed. On November 21, 1996, a demonstration was organized, during which a leaflet titled “Save the 21” and another document, “The Call of the 21,” were distributed. On the eve of this mobilization, the City of Paris announced the withdrawal of the real estate project. The day of the demonstration turned into a great neighborhood celebration, marking four years of struggle. In January 2012, the City of Paris entrusted the management of the alley to Semaest through a 25-year emphyteutic lease.

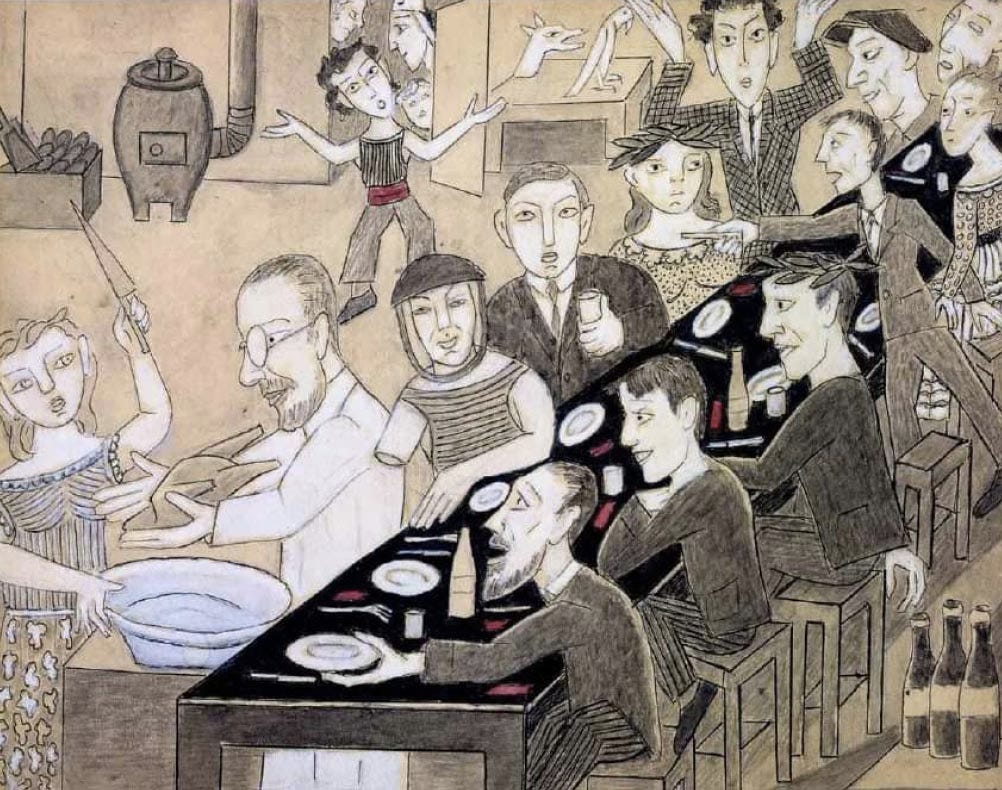

Marie Vassilieff, Banquet Braque, Sunday, January 14, 1917, gouache on cardboard, 24 × 30.5 cm. All rights reserved, Claude Bernès collection.

Number 21

was once a post house where the horse teams were changed for those traveling to Brittany. The only visible remnants today are the two stone markers at the end of the alley, which were originally located on the avenue. On January 19, 1869, Jean-Adolphe Roux, a lawyer at the court, became the owner of all the buildings. In 1868, before entering the passage, the coal merchant Gabrillargues occupied the right-hand shop, and Mr. Lepage, a cooper, occupied the left-hand shop, succeeding Mr. Drouville. The walls were made of frames and cladding covered with tarred cardboard. As early as 1899, the owner modernized the place by installing a complete sewer system, completed in 1901 by the architect Mr. Charpentier. After his father’s death in 1899, Joseph Roux decided to transform the place into an artists’ community. In 1900, he acquired a series of pavilions from the Universal Exhibition. The buildings were restructured, and the use of metal beams gave it an industrial character. In 1920, the Roux family sold the alley to Eugène Philebert Maisonny. In 1922, the roofing company of Etienne Maisonny moved in. In 1946, one of his descendants, Madame Lynka Maisonny, became the owner. Upon her death in 1990, faced with high inheritance costs, her children were forced to put Number 21 up for sale. The Town Hall of the 15th arrondissement preempted the property and presented a real estate project in 1992. This project was rejected by the residents of the alley. The association “Friends of 21 Avenue du Maine,” presided over by Maurice Tinchant, was supported by many artists and personalities, including Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, Robert Doisneau, Juliette Binoche, and Frédéric Mitterrand. A petition circulated, the press took up the issue, and a long battle ensued. In 1996, after two successive legal appeals, the City of Paris agreed to abandon the total destruction of the alley and preserve part of it. The creation of the Montparnasse Museum in the preserved premises of Marie Vassilieff was proposed. On November 21, 1996, a demonstration was organized, during which a leaflet titled “Save the 21” and another document, “The Call of the 21,” were distributed. On the eve of this mobilization, the City of Paris announced the withdrawal of the real estate project. The day of the demonstration turned into a great neighborhood celebration, marking four years of struggle. In January 2012, the City of Paris entrusted the management of the alley to Semaest through a 25-year emphyteutic lease.

Marc Vaux at the door of his first studio, 23 Avenue du Maine, Paris, 1919, Anonymous, © Centre Pompidou – Mnam – Bibliothèque Kandinsky – Marc Vaux Collection.

The Alley and Its Occupants

Marie Vassilieff (1884–1957) settled in Paris in 1907. She was a secretary and then director of the Russian Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1911, at 54 Avenue du Maine. In 1912, she had to give up her position as director to a man, the sculptor Sergei Bulakovsky. She moved to Number 21, established her studio, and opened her own Academy (1912–1929). Fernand Léger gave two lectures there in 1913 and 1914. In February 1915, she opened the Artists’ Canteen, where artists could get a meal of broth, meat, vegetables, salad or dessert, coffee or tea for 65 cents, and wine for an additional 10 cents. In January 1917, Marie Vassilieff and Max Jacob organized a banquet for Georges Braque, who had been demobilized, with Matisse, Blaise Cendrars, Picasso, and Modigliani (who was not invited). In 1918, suspected of being a Bolshevik spy and an intimate of Trotsky, she was arrested and placed under house arrest in Meulin with her son Pierre. After her release, she received support from Paul Poiret, who commissioned her to design the bottle for the perfume Arlequinade in 1923. In 1924, she moved to 37 Rue de Froidevaux. She decorated two pillars of the café La Coupole in 1927. She spent her final years in the artists’ retirement home in Nogent-sur-Marne and died in 1957.

Next to her studio was Marie Blanchard (1881–1932), whose real name was Maria Gutierrez Cueto y Blanchard, a Spanish painter. The two women were known as the “two Maries of painting and hardship.” In 1909, she received a grant to continue her training in Paris. She worked with Hermen Anglada-Camarasa and Kees Van Dongen. In 1916, she moved into the alley, forming friendships with Juan Gris and André Lhote. In 1912, the Montparnasse Academy opened at the end of the alley; Marcel Gromaire and his friend Despierre taught on the first floor. In the 1920s, Robert Nabeyrat set up his printing shop at the end of the alley, joined by his younger brother Raymond and later by Michèle, Raymond’s daughter. In 1922, Etienne Maisonny became the owner of the alley and opened a plumbing and heating business next to Nabeyrat’s printing shop. Over time, upholsterers, woodworkers, and antique furniture restorers succeeded him.

In 1930, the architecture studio Gromort and Arretche of the Grande Masse des Beaux-Arts of Paris took over the premises of Marie Vassilieff’s canteen, training the great architects of the time.

If art was a common identity among the occupants of this alley, celebration was another. Every year, for the Rougevin festival, the handcarts of the Beaux-Arts were built in the alley. Once decorated, the procession went to the Place du Panthéon, where they were burned. The famous Bal des Quat’Z’Arts was held there. In January 1939, Roger Pinard, aka Roger Pic (1920–2001), moved into Number 2. His neighbor, Jean-Marie Serreau (1915–1973), occupied a space called the Refuge des Compagnons, a theater troupe from 1938 to 1952. Pierre Jamet inspired Pic’s love for photography. Initially an actor, then a theater company director, Pic became a photographer, filmmaker, war correspondent, and television director. Serreau staged works by major authors (Pirandello, Brecht, Ionesco, Beckett, Genet), with Pic as stage manager. The war and occupation disrupted this creative momentum. Pic lived in hiding to avoid the STO and the Vichy regime’s youth camps. He joined Serreau in 1944 in a structure called “Travail et Culture.” At the time, photographs of actors were staged offstage. Roger Pic invented on-stage photography in 1945, favoring authenticity. Serreau left his studio to Roger Pic in 1953.

In 1946, the German painter Francis Bott (born Ernst Bott, 1904–1998) and his wife Maria Gruschka, aka Manja, moved in. In Prague, Oskar Kokoschka encouraged him to paint. Settling in the alley in 1946, he developed an informal style, applying paint with a spatula and creating Bott Blue (Bott-Blau). In 1947, Georges Visconti (1919–2019) moved in. Initially a theater man and a student at the Geneva Conservatory, he joined Roger Blin’s troupe after World War II. He frequented Jean Souverbie’s studio and dedicated himself to painting and engraving.

In 1919, Marc Vaux (1895–1971), a photographer and friend of Montparnasse artists, moved to 23 Avenue du Maine. In 1927, he moved to 114 bis Rue de Vaugirard. In 1946, he founded the Mutual Aid Center for Artists and Intellectuals, a canteen-gallery at 89 Boulevard du Montparnasse, continuing Marie Vassilieff’s canteen. In 1951, he opened the Montparnasse Museum at 10 Rue de l’Arrivée–21 Avenue du Maine in the former Gromaire Academy. It was inaugurated on April 28, 1951, in the presence of Cléopâtre Bourdelle and Paul Fort. A miller’s ladder allowed access to the alley through the museum. In 1963, construction around the Montparnasse station blocked access to the museum from Rue de l’Arrivée. At 68, he decided to close the museum. The space later became Botero’s studio and is now occupied by photographer Eric Neveu.

In 1957, the poet, sculptor, and painter Jean-Pierre Duprey (1930–1959), close to the Surrealists, occupied the studio on the first floor to the left, where he committed suicide in 1959. From 1972, Annick Le Moine and her partner Annette Englebert created a contemporary art studio in the former premises of Marie Vassilieff. It was multidisciplinary and hosted Krasno, Carolyn Carlson, Claude Bellegarde, Bernard Heidsieck, and others. In 1976, the International Sound Poetry Panorama was discovered there, where John Giorno gave his first public reading in France. After Le Moine’s death in 1987, Charles Sablon (Charmy l’Envers gallery, Rue Lhomond) and Lynka Maisonny’s grandson took over the studio. It hosted Jean-Max Albert, Claude Lagoutte, Béatrice Casadesus, Jean Degottex, and others. On the ground floor, a yogurt shop that had been there since the 1950s remained active.

“Villa Marie-Vassilieff” [archive], on www.v2asp.paris.fr (accessed November 25, 2016)

The Brazilian sculptor of Polish origin Frans Krajcberg (1921–2017) settled in 1950. He studied engineering and took classes at the Leningrad Academy of Fine Arts. He left the city in 1941 and joined the Polish army in 1942. In Stuttgart, he attended Willi Baumeister’s Bauhaus course, who wrote him a letter of recommendation for Fernand Léger. Hosted by Chagall in Paris, he left for Brazil in 1947 on Léger’s advice. He received the award for Best Brazilian Painter in 1957. In 1978, with Pierre Restany and Sepp Baendereck, they traveled up the Rio Negro. During this trip, Restany wrote the Manifesto of Integral Naturalism or the Rio Negro Manifesto.

His friend and neighbor, the Italian sculptor Gigi Guadanucci (1915–2013), arrived in Paris in 1953 after leaving fascist Italy and joining the French Resistance. In Montparnasse, he associated with Giacometti, Zadkine, and César.

Maurice Tinchant Tran-Trong moved into Jean-Pierre Duprey’s former studio and the right-hand street shop in 1974, previously the “Atelier for Germaine Monteil Perfume Windows.” He opened his cultural advertising agency, Publicité Tinchant, and the companies Pierre Grise Productions (Rivette, Akerman, Iosseliani, Fillière, Carax, Monteiro, D. Schmid) and Pierre Grise Distribution (Guédiguian, Sokourov, Michelangelo Frammartino).

Marie Vassilieff in her studio at 21 Avenue du Maine, 1922. Photograph by Agence Trampus, all rights reserved, Claude Bernès collection.

Since 1984–85, Eric Darmon and Xavier Gros, producers and directors, opened the Mémoire Magnétique space.

In 1985, William Foucault, an interior architect, decorator, and antique dealer, operated his shop on the ground floor of the right wing. Alain and Nad Cianferani set up the Lieu-Dit floral decoration workshop. Bouchaïb Hallaoui opened his garage in 1984. Nearly thirty years earlier, a garage had existed in the 1930s, just behind the alley on Rue de l’Arrivée. A poorly extinguished cigarette allegedly caused the station to catch fire in the 1960s, leading to its relocation to Avenue du Maine. Frédéric Pinard, son of Roger Pic, occupied one of his father’s studios, as did Nicolas Meunier, his grandson, and Marie Dietrich.

In 1996, the Penta photogravure company vacated 550 square meters, divided into several spaces. After two years of negotiations, new occupants—symbolizing renewal—moved in. The alley was reborn with these newcomers, reopening to the public and hosting annual celebrations. Théâtre Express (Bertrand Saint and Claude Chrétien) became a center for theatrical research, training, and creation.

The Awazu and Ponfilly Architects agency (Kozo Awazu and Jean de Ponfilly) also moved in. Above the garage, Nicolas Pétrovitch, an architect and Prince of Montenegro, set up his agency and organized the Biennale of Contemporary Art in Cetinje.

On the ground floor beneath the theater, Cannelle Tanc and Frédéric Vincent opened Immanence, an art center showcasing diverse contemporary artistic fields (Édouard Levé, Grégory Chatonsky, Gülsün Karamustafa, Robert Filliou, Agnès Thurnauer, Gladys Bourdon). In 2008, they launched Archive Station within Immanence, a documentation center focused on artists’ books.

Marie-Christine Damiens, a film publicist, and Les Films au Long Cours, a production company specializing in short films by Olivier Berlemont, developed their projects there.

Daniel Moquay, married in 1968 to Rotraut (widow of Yves Klein and sister of Günther Uecker of Group Zero), established Tête à Tête Arts in the former lithography printing workshop.

On May 27, 1998, the Montparnasse Museum opened in the former location of Marie Vassilieff’s canteen. Founded by Roger Pic and Jean-Marie Drot, its inaugural exhibition celebrated Marie Vassilieff. Many exhibitions followed, honoring foreign artists in Montparnasse, poets, and Parisian cultural life. Most of these exhibitions were curated by Sylvie Buisson, the museum’s general commissioner. The Montparnasse Museum closed its doors on September 30, 2013, by decision of the City of Paris.

For one year (February 2013–2014), the Adresse Musée de la Poste occupied the space. In September 2015, the City of Paris invited the Bétonsalon association to establish their second art space, named Villa Vassilieff. The City of Paris closed the venue on December 31, 2020, and in 2021, appointed the Aware association—Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions—founded in 2014 by art historian Camille Morineau, to take over the space.

21 Avenue du Maine

Known as the alley, cul-de-sac, or pathway, is now officially registered as Villa Vassilieff. It is a dead-end alley, no longer a passage as it was until the 1960s. Despite wars, real estate projects, and life’s ups and downs, it remains a vibrant part of Paris’s cultural landscape. It has witnessed the artistic upheavals of the 20th century, from the early avant-garde movements and the School of Paris to sound poetry and contemporary art. It stands proud, ready to welcome the public, passersby, and the curious. It also embodies the blending of genres.

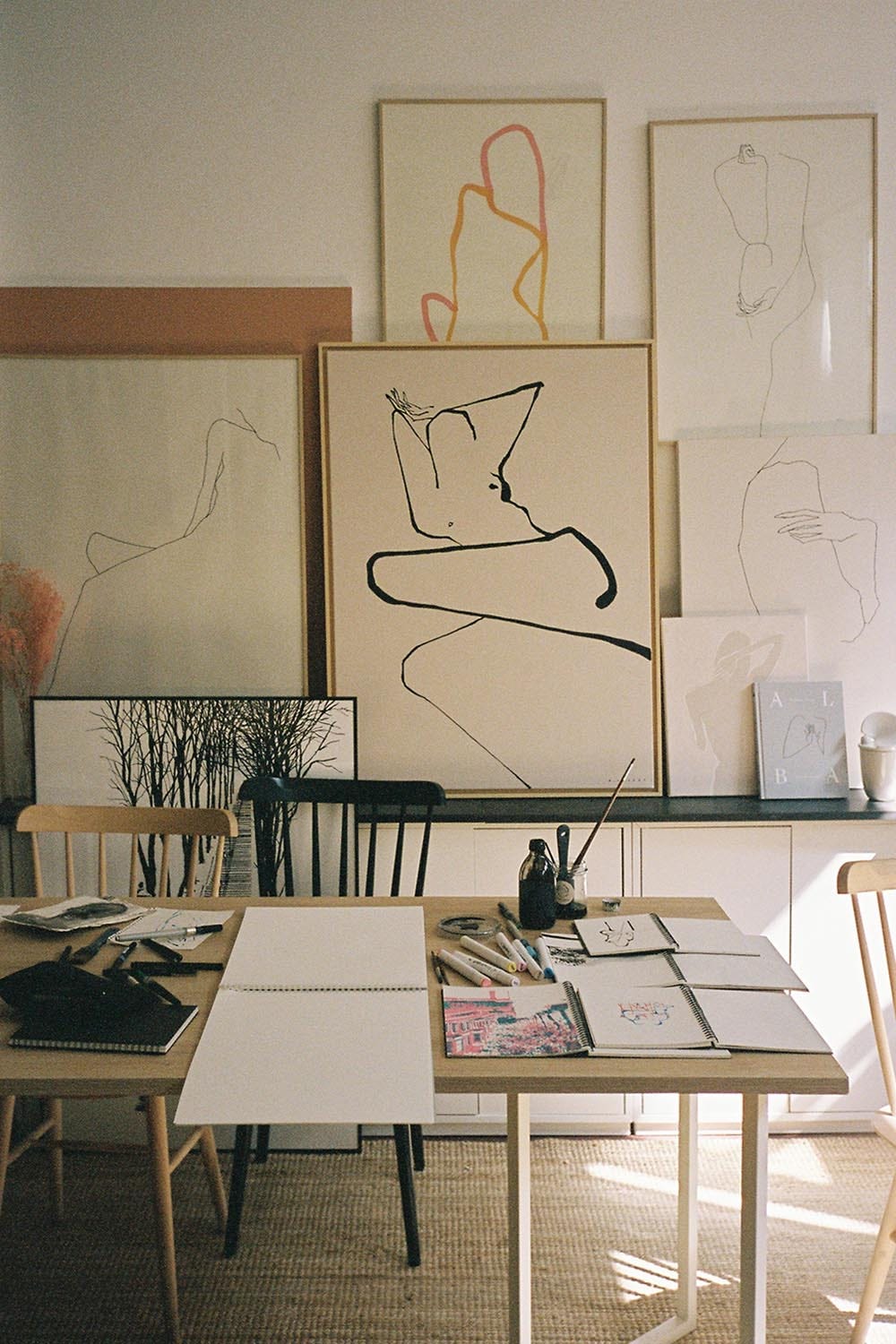

Today, the Espace Krajcberg houses a collection of his sculptures and welcomes contemporary artists committed to environmental advocacy. Clémentine Giaconia, myself, and our publishing house Grammatical moved into his former studio in 2019. At the end of the alley, you can still find the Yves Klein Foundation, the Immanence Gallery, an antique dealer, Mémoire Magnétique, Mina the Japanese florist who decorates the Café de Flore, a theater workshop, short film production companies, an embroidery studio, and one of the studios of photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand, who arrived recently, along with a few residents.

We are all united in our own ways to perpetuate the artistic and vibrant spirit of this hidden gem in the 14th arrondissement. Today, thanks to all its occupants, it looks to the future—focusing on ecology, gender equality, and promoting young artists, filmmakers, graphic designers, and decorators. Behind its century-old appearance, this alley symbolizes the future of a city: hospitality and sharing.

our eponymous studio with Clémentine Giaconia, located in 21 avenue du Maine, 75015 Paris

Love from Paris